OCBC Building

I.M. Pei

2 July 2019

Khoo Teng Chye, Executive Director, Centre for Liveable Cities, Ministry of National Development | Past Chair, ULI Singapore [This article was first published in CLC Insights]

Since the 1960s, Singapore has been transformed from an overcrowded urban slum into one of the world’s most liveable cities, with a population density that has almost tripled. Urban planning — so vital in building the city — also impacted the real estate industry. How can the industry become more proactive in shaping Singapore’s future? This question can be explored through the four main phases of how urban planning and real estate development have evolved together over the decades.

Four phases of how Singapore has evolved since the 1960s.

Source: CLC

In the 1960s, faced with overcrowded slums and fragmented land ownership, the government’s top priority was solving the chronic, very serious housing problem and ensuring enough land for new towns and urban renewal. With a successful public housing programme, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) built some 50,000 flats in its first five years, more than the 23,000 flats built by the former Singapore Improvement Trust since 1927.*

Then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, in a parliamentary debate, outlined two broad principles for amending legislation on land acquisition: (1) No private landowner should benefit from development at public expense; and (2) Prices paid on acquisition for public purposes should not be higher than what the land would have been worth otherwise. “Increases in land values, because of public development, should not benefit the landowner, but should benefit the community at large,”^ he said.

Hence, the Land Acquisition Act was amended in 1966 to strengthen government powers to acquire land, and to limit compensation. Much of the land the government now owns was acquired by development agencies: HDB for housing, JTC for industrial estates, Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) for the Central Area, Public Utilities Board for utilities, Port of Singapore Authority for the port and Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore for the airport. From 1960 to 2007, land owned by the public sector doubled from 44 per cent to over 85 per cent.

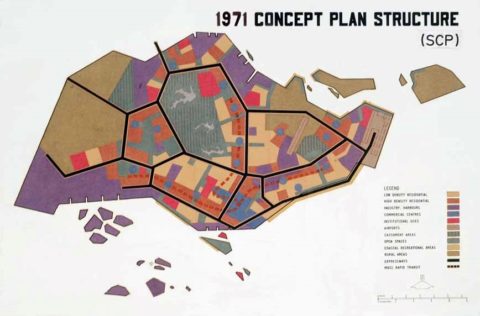

Concept Plan 1971 outlining Singapore’s urban structure for a modern city and safeguarding land for development

Source: URA

Once the government became the biggest landowner, it began building new towns and redeveloping the Central Area comprehensively and rapidly. A United Nations Development Programme team, working with a young team of planners, architects and engineers here, drew up the Concept Plan in 1971 after four years of study — Singapore’s first strategic land use and transport blueprint for the urban structure of a modern city.

The real estate industry, quite small then, did not play a significant role in Singapore’s development. The government was nevertheless concerned that, with higher zoning and plot ratios, owners of private developments would enjoy excessive profits. Hence, the development charge, a betterment tax, was introduced and conscientiously implemented. This was unlike in Britain, where the idea came from, as a lack of political consensus there restricted its implementation.

The urban planning system then was inherited from the colonial-era Town Planning Act, and a 1958 master plan too rigid and inappropriate for a rapidly growing Singapore. Based on the Concept Plan, agencies drew up their own plans for HDB towns, JTC industrial parks, URA’s Central Area plans and other infrastructure plans. The Planning Department’s main task was to ensure that land was carefully safeguarded for new towns, the Central Area, roads, and subway and utility reserves.

The task of urban renewal now began in earnest, as URA became planner and master developer of the Central Business District.

The key person responsible was Alan Choe, my first boss at URA, a young, dynamic architect-planner who learnt a lot about urban renewal in the West, especially from the Boston Redevelopment Authority. He adopted some of Boston’s methods, wisely adapted to suit Singapore. As an architect, he developed very detailed urban design guidelines for places like Shenton Way, Golden Shoe District, the Orchard Road belt and the Golden Mile strip.

URA Sale of Sites

Source: URA, Changing the face of Singapore through the URA sale of sites, 1995, Pg 5

What distinguished Singapore’s approach from many other cities was how the private sector was involved to implement the plan through URA’s Sale of Sites programme (now the Government Land Sales programme). It was creatively conceived to involve developers through a transparent tender process. As long as developers built according to guidelines, they had no problem obtaining planning approval. To attract bidders, incentives such as property tax concessions as well as financing through a 10-year instalment plan were given. All these significantly derisked projects by reducing uncertainty and approval time.

However, even with these incentives, businessmen had to be persuaded to delve into the risky business of real estate. Choe told of how he had to call on business people like S.P. Tao, a shipping tycoon then, to tender for URA sites. Choe had to sell the new city vision, how the government would make it happen in partnership with the private sector, with URA providing the planning vision and guidance, putting in infrastructure and coordinating overall development as master developer.

This was Singapore’s Public-Private-Partnership approach to urban renewal. The approach quickly gained confidence among developers risking their capital, who saw the tremendous upside of helping to build a rapidly growing city.

The sale of sites programme was a key instrument to encourage certain types of development, such as offices for financial institutions, shopping, entertainment and hotels along Orchard Road and the Havelock Road belt. It also promoted high-density living, with a new housing typology in high-rise condominiums with green spaces and community facilities based on planning guidelines.

Again, Choe, as an architect, introduced the idea of awarding sites by giving design very serious consideration. For developers, the stakes became so high that they hired top international architects like I.M. Pei (Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Building), Kenzo Tange (Overseas Union Bank Centre), Paul Rudolph (Concourse) and John Portman (Marina Square).

OCBC Building

I.M. Pei

OUB Centre

Kenzo Tange

Concourse

Paul Rudolph

Marina Square

John Portman

At that time, URA’s guidelines were not publicised, so there was uncertainty over planning requirements. This lack of transparency made public officials susceptible to corrupt practices. Property had a boom-and-bust market, with the government releasing more land during periods of boom and withholding sales when prices fell. Attractive financial incentives also created a volatile market.

Things came to a head, and Member of Parliament Tan Soo Khoon, in a famous speech in 1986, called the property market a “casino”, with URA as “banker”. This was after a property market crash when some developers could not find funds to continue development, and returned the sites to URA undeveloped. A Cabinet minister committed suicide when investigated by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau.

The new city was being built in partnership with the private sector, but the planning system needed to catch up. These events prompted a serious overhaul of the planning regime when S. Dhanabalan took over as National Development Minister in 1987.

The changes were quite sweeping, making the system more open, transparent and stable. I was part of the team that brought about many of these changes, as MND’s first Director of Strategic Planning, working closely with Lim Hng Kiang, then Deputy Secretary.

URA took on a clearer role as planner and regulator, and no longer as developer. It returned most of its land holdings. Zoning was simplified and plot ratio calculations streamlined with the abolition of net floor area, so that only one parameter, gross floor area, was used. This removed a lot of administrative effort and uncertainty under the old regime. A team led by MND created what is now known as the development charge table, which tells developers upfront what they must pay.

Headline ‘Developers give up two URA land parcels’

Source: Singapore Monitor, 28 April 1984

Full article here

Headline ‘Option for Pontiac to revive Rahardja Centre project’

Source: Times, 3 Aug 1989

With the new transparency, the real estate industry began to attract international capital, and new instruments like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which were pioneered by Singapore in this region, resulted in a more mature and sophisticated capital market.

All financial incentives for sale of sites were withdrawn as, by now, the banking and finance industry had the confidence and expertise to finance development. Land was released in a steady stream rather than along with market vagaries.

With the new transparency, the real estate industry began to attract international capital, and new instruments like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which were pioneered by Singapore in this region, resulted in a more mature and sophisticated capital market.

However, a surplus of capital internationally and Singapore being seen as a safe haven meant that the government had to periodically intervene, especially in the residential property market, with cooling measures.

The 1991 Concept Plan — unveiled as “Living the Next Lap” — envisaged building a northeast corridor and decentralising with regional and subregional centres. The master plan became a forward-looking and public plan with the introduction of Development Guide Plans (DGPs), which clearly expressed planning intentions for 55 DGP areas, with clear zoning, plot ratios and other detailed urban design guidelines, so that developers knew exactly what they were allowed to build.

There was also a continuing focus on building a liveable, sustainable city of character.

There began in the late 1980s a strong emphasis on retaining built heritage. URA did extensive surveys of historic areas, and drew up a conservation master plan and strategy which involved URA becoming the conservation authority, setting guidelines for conserving buildings, gazetting buildings and districts, and bringing in the private sector, again using the sale of sites mechanism. Projects such as Clarke Quay, Bugis Junction and Chijmes were sold, as were many shophouses in Chinatown, Little India and

Kampong Glam.

The Singapore River master plan saw the creation of a district of old warehouses adaptively reused for shopping, offices, hotels and homes, juxtaposed with modern buildings. New modes of sale were experimented with, such as auctions, the two-envelope system, and fixed land prices for the two integrated resort projects. The Marina Bay Financial Centre (MBFC) was sold using an option pricing method to reduce development risk, as the objective was to sell a big piece of land for master development by the private sector.

Clover By The Park condominium next to Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters features at Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park.

Source: littledayout.com

To advance sustainability and make the city greener and more liveable, more emphasis was placed on promoting Green Mark buildings and high-rise greenery. The Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters programme saw strong interest in creating water projects, which commanded a premium. Projects along the waterway in Punggol Eco-town all began to include variations of “water” in their names.

The sale of sites programme was also used to promote sustainable green buildings, with sites sold by tender being required to achieve a minimum Green Mark in selected strategic areas such as Marina Bay, Jurong Lake District, Kallang Riverside, Paya Lebar Central, Woodlands Regional Centre and Punggol Eco-town. Today, sites in strategic areas are required to be designed and built using the Design for Manufacturing and Assembly and Building Information Modelling systems.

As Singapore has come a long way as a well-planned, liveable and sustainable city, the real estate industry, now highly sophisticated and professional, also continues to innovate.

The transparency of a forward-looking master plan also gave rise to a new phenomenon of en-bloc development, flourishing especially during market upcycles, as owners of strata titles and even landed properties banded together to sell their properties for redevelopment. This helped to realise the master plan, while government policy facilitated this with lower thresholds of ownership.

As Singapore has come a long way as a well-planned, liveable and sustainable city, the real estate industry, now highly sophisticated and professional, also continues to innovate.

But what’s next for Singapore — how will the city develop? How should we plan for it? How can the real estate industry help to shape the future?

As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said, “we are not done building Singapore yet”.** There are many exciting new opportunities at Marina Bay, Greater Southern Waterfront, Jurong Lake District and, further down the line, Paya Lebar when the airbase is closed. Exhibitions on these plans, such as the one on the draft 2019 Master Plan at the URA Centre, will help people understand the challenges of building a liveable and sustainable city with all its constraints. While some precious greenery will be developed, many new ideas such as nature parks will more than replace the losses. To face new challenges, Singapore has to continue to innovate systemically, like before.

What are these new challenges?

Climate change, changing demographics (especially ageing and a more diverse society), rapid technological change, social media, lifestyle trends towards co-working, co-living, a sharing economy with ride-sharing, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence and big data.

Beyond the Master Plan, in order to solve the problems these challenges will bring, and create new opportunities, more systemic ideas are needed. For example, building a city in nature, or a city for all ages.

But what is the role of the real estate industry? For universities, research and education in urban systems is critical. Singapore has built up a significant store of knowledge, which should be shared, and used to create new knowledge. Our universities are actively undertaking urban systems research with CLC and other agencies with studio projects such as in Tampines, one-north, and Orchard Road. The National University of Singapore (NUS) is rather proud that its real estate department is just about the only one in the world that is part of the architecture and urban planning school rather than the business school.

CapitaLand-CDL Joint Venture for Prime Site in Sengkang Centre.

Source: CapitaLand Limited (2019). CapitaLand-CDL joint venture wins prime site in Sengkang Central

But what role can developers and real estate financial institutions play in shaping the city? I sense that the industry is beginning to take a much broader view of their role. URA has received strong support for its Business Improvement Districts pilot schemes, where property owners come together to do place management for neighbourhoods. Orchard Road Business Association is active in reshaping Orchard Road. Developers are becoming master developers, rather than being led by government. In Sengkang, CapitaLand and City Developments Limited are building an integrated commercial-cum-community development including a

community centre and hawker centre.

CLC and URA sponsored the Urban Land Institute (ULI), an international organisation of real estate professionals, to bring in an international panel to give views on how the private sector can participate in Jurong Lake District. This intensive process included interviewing 60 industry professionals from government, the private sector and academia. New forms of partnership are developing between the public and private sectors.

Internationally, the industry is spreading its wings. Companies are doing city master planning in Asia, Africa and Middle East. Singapore has major integrated city and township projects in Suzhou, Tianjin, Guangzhou and Amaravati. To offer an integrated package, it is also essential to involve smaller companies and other parts of the real estate value chain, such as legal and financial services.

Infrastructure Asia was set up by Enterprise Singapore to promote Singapore as an infrastructure finance hub. There is good potential for the industry to grow, as the region is urbanising very rapidly and the need for well-planned, liveable cities is urgent. Singapore is often looked upon as a model, but how can we better “sell” brand Singapore and public and private sector

expertise as an integrated package?

Singapore was built primarily by public sector agencies in the earlier years. Later, the private sector became an active partner, producing a boom period. This was followed by a period of putting in place a good urban planning system and building a highly sophisticated real estate industry.

Can Singapore now become a global hub to take to the world this new partnership between the private and public sectors in creating urban systems solutions? That is our collective challenge.

Notes

* Savage, Victor, and Eng Teo. “Singapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing Change.” Singapore Journal of Tropical

Geography, vol. 6, no. 1, 1985.

^ Singapore Parliamentary Debates. (10 June 1964). Vol. 23, Col. 25. See also observations by then-P.M. Lee Kuan Yew and then Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker during the second and third readings of the Land Acquisition (Amendment No 2) Bill in 1964-66 and Singapore Parliamentary Debates. (16 June 1965). Vol. 23, Col. 811; and (26 October 1966).

Vol 25. Col 410.

** Lee, Hsien Loong. “National Day Message 2018.” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 8 Aug. 2018, www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/national-daymessage-2018.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Choy Chan Pong and Kwek Sian Choo for their inputs; as well as Phua Shi Hui for research assistance, Koh Buck Song for editing the text and Ng Yong Yi for layout design. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of National Development. If you would like to provide feedback on this article, please contact [email protected].

About the Author

Khoo Teng Chye is the Executive Director for the Centre for Liveable Cities, Ministry of National Development (MND), Singapore. He was formerly the Chief Executive of PUB, Singapore’s National Water Agency and Chief Executive Officer/Chief Planner at URA.

Khoo Teng Chye is the Executive Director for the Centre for Liveable Cities, Ministry of National Development (MND), Singapore. He was formerly the Chief Executive of PUB, Singapore’s National Water Agency and Chief Executive Officer/Chief Planner at URA.

Don’t have an account? Sign up for a ULI guest account.